The gaming continued this week. Other than that, I embarrassed myself in the frisbee golf season openings and helped some friends with their game design projects. The latter is usually pretty casual in that it’s normally not scheduled or really planned for, but it can take significant time, nonetheless – and produce significant results.

Consulting in game development

Tabletop roleplaying games are usually designed by a single designer working in concert with a bunch of development buddies who help out in two distinct ways: playtesting and studio critique. The latter is something of a forte of mine: I analyze well, and have opinions and ideas, so I like reading a game text and offering my thoughts. It’s by no means guaranteed that a studio critique by a given person will be useful for you, as it may be that our experiences and interests are too divergent for me to get a good handle of what you’re attempting to do, but often we’ve had good experiences in this area. At worst you can just shrug and accept that the creative chemistries don’t always work out either due to interpersonal match-ups or it being the wrong point in the project to seek outside perspective.

Getting good results from a consult is a two-way street, of course. In my experience the game designer’s motivation towards development is often a key issue both as a precondition in getting anywhere and as a potential outcome of a good studio critique. Ideally you come in to consult on a project when the designer is mentally in a place where they are open to new ideas, and open to be reinspired by their project. While a good studio critique may include some concrete answers to specific design conundrums, often the most important part is indeed critical in the literal sense of art critique: it’s a philosophical treatment by an outside pair of eyes on what the purpose of the work is, and how it is, or must be, shaped to achieve its aims. In the best case this outside perspective inspires the designer towards a clearer vision of their work, whether it’s the same or different from what the critic sees.

I did some pretty heavy studio critique and playtesting for Subsection M3 over the winter, but as that project’s been pretty stalled on the design end, I haven’t concerned myself with it for a bit now. Instead, this week I’ve gotten my hooves on a couple of other games in development.

Game Development: Varangian Way

Petteri Hannila, the designer of Tales of Entropy, has been brooding over an ambitious new game for a couple of years now – ever since finishing with Entropy, really. The new game’s sweeping subject matter concerns nothing less than the viking era of Eastern Europe, a topic often ignored by English-language historiography in favour of the North Sea viking adventures. In Petteri’s game the players take on roles as Swedish explorers, merchants and raiders who might in their time manage to conquer the patchwork lands of Gardarik, setting the stage for the emergence of the Rus polities – it’s a game about the birth of Russia, in other words.

As I’ve discussed before, I enjoy a particularly sympathetic working relationship with Petteri, so it’s always a pleasure to see him advancing his project. I’m pretty comfortable supporting him morally by praising the hypothetical greatness of the game once it emerges, and by describing the ways I imagine it working, while leaving the annoying details of how to make it work up to him. It’s his project, after all.

The pandemic situation has apparently left Petteri with an unusual amount of free time, which has translated into him tackling the Varangian Way development anew this last week. We’ve been discussing the game’s conflict resolution and content-generation engines, and there’s some initial agreement about setting up a playtest at Petteri’s rpg online rpg club later in the spring.

Game Development: Flame, Star and Night

A second game in development has been attracting my attention this week as well: Tommi Horttana’s a Finnish expatriate gamer whom I got to know in Helsinki earlier this decade, and he’s apparently the latest victim of the game design bug. Flame, Star and Night is a delightful Forge-style drama game that focuses on slice of life, lifestyle drama: the game’s rules are dedicated to following the seasonal toils and travails of an iron age village in a Northern European mythic milieu. A particular virtue is that when I say slice of life, I really mean that: the game doesn’t have dramaturgical scene framing like your average viking village game does, and therefore the story doesn’t automatically hop and skip its way through the years, ignoring the farm work and such. No, in this game you move season by season, having to choose what projects ranging from survival to luxury developments your villagers prioritize. The dramatic core conceit is to follow entire decades-long life arcs of characters, seeing what metaphorical treasures they choose to develop, retain and protect in a harsh land that often demands your best to spare the future.

Tommi’s development has been advancing with alacrity, he got a playtestable package together in a couple of days after getting motivated to write. This was no doubt helped out by the fact that the game’s core conceits are based on a video game design document Tommi had put together earlier – his actual job is in video games, so that’s natural enough. Still, the first draft is already sharp and makes me want to play, so I’ll have to try to get this into the schedule somehow. I get the impression that Tommi’s been inspired by the various discussions we’ve had about gaming and its theory over the recent months, but for the most part he seems to have this so well in hand that the only consultation he needs is a cheering section.

I’ll also note that these two active game design projects share a specific factor: the designers have been playing with us at rpg club Hannilus. I should maybe try to get more prospective designers to play with us, it’s clearly an inspiring scene. Get lots and lots of game designs under way, so maybe some of them reach the goal and become products of some kind, to be shared and treasured by a wider audience.

Monday: Dragon’s Castle

Speaking of gaming at Hannilus, we’ve continued with our weekly two campaign standard. The Dragon’s Castle continued on its adventurous course on Monday: we had a general-interest monster fight with Mermen in the interest of increasing group facility with the conflict resolution rules, and then the actual meat of the Chapter in the form of the Flying Dutchman making an appearance.

The story has moved to the Danubean delta at this point, with the PC slayers wielding handy control over the sea by the virtue of the Temperance, the ambiguously legal warship that captain Summers came with to the area. The naval theme was naturally compounded by this great clash of the titans, with the flower of British ship-building (and Morisco crewing) set to contest with the skeleton crew of the undead ship of fools, the might Dutchman. I imagine that we’ll leave the naval stuff behind when the heroes finally manage to breach their way into Castlevania proper, but for now we’re firmly in the age of sail naval adventure territory.

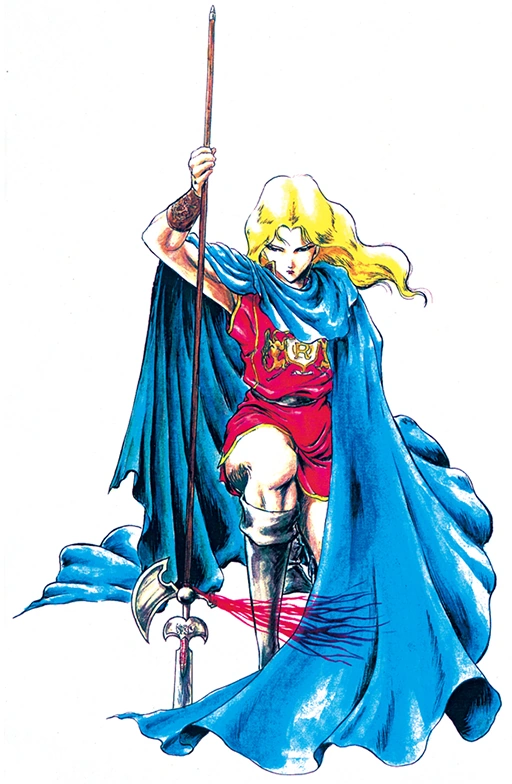

I got the opportunity to introduce captain Eric LeCarde as yet another sort-of-vampire-slayer (a “named NPC” as opposed to less significant non-player characters in the story) and prospective boss monster: LeCard is, like captain Summers, a Spanish nobleman disappointed in the static and ever-moribund nature of his homeland’s society. As an international adventurer he’s a sort of a dark mirror image for Summers, as LeCard seems to see nothing wrong in giving his allegiance to the Count in exchange for the opportunity to sail the greatest ship known to the age of sail, the aforementioned Dutchman. Bolstered by the dark dragonic sciences the flying ship and its undying crew have enabled captain LeCarde to accomplish all his dreams and more.

We ended the session at something of a cliff-hanger, as the heroes betrayed the parlay they’d set up with LeCarde, setting themselves up for a hilarious boss fight: after firing a mine boat on the hull of the Dutchman in the middle of negotiations, the heroes were rowing away from the struggling ghost pirate ship under the cover of darkness. It may have been my favourite moment of the game when LeCarde displayed his fleetness of foot by busting out a classical wuxia maneuver: he grabbed his spear and jumped off his ship, punching off the wall of the castle and proceeded to run over the river after the dishonorable malcreants. (The action choreography in this game isn’t arbitrary, so I didn’t just choose for him to be able to do this. Eric LeCard is a tough hombre!) That’s where we left it for the night, meaning that the first thing we have waiting for us next time around is a boss fight.

Thursday: Fables of Camelot

On the Arthurian front, on the other hand, we had a rather grueling, emotionally heavy time with the classic romance of the Green Knight. We had a bit of a different crew than before, with one particularly chivalric knight (and a player prone to chivalry) missing, while another particularly practical Saxon bachelor knight (think grim Japanese wandering ronin) joined the fray. This shift in the moral and emotional tone of the group proved extremely pertinent in this particular adventure, as the Green Knight is a particularly, exceptionally moral tale for a chivalric romance. While the Grail Quest we did last time is actually not a moral story at all despite all the pious posturing, this time around it mattered quite a bit what the individual knights thought about honor and duty.

The short version of the Green Knight story (in my interpretation): a modest rural knight called Lord Bertilak de Hautdesert wants to test the knights of the Round Table, for he doubts the High King’s Golden Vision, the rule of chivalry he claims as the foundation of Camelot’s rule and justification. Morgana le Fay convinces Bertilak to don the disguise of the eldritch Green Knight and challenge the Round Table to a beheading game: first his quarry would strike at the Green Knight, and then, a year and a day later, they would meet and the Green Knight would give an answering blow. The Green Knight is of course full of eldritch vitality, so much so as to be able to catch his own head and replace it, thus surviving the morbid exercise. He left young Gawain in quite a pickle, as now he was honor-bound to meet with the Green Knight at the Green Chapel to finish the game!

Lord Bertilak’s plan was for Gawain to come to the Green Chapel, which was close to his home of Hautdesert, and visit him at Hautdesert, where he could further test the virtue of the young knight. Should he succeed in the tests of virtue (involving some salacious cuckolding stuff with lady Bertilak), the Green Knight would spare the young man; elsewise, the story might end in him doing justifiable homicide to a man who broke the laws of hospitality in his own house. A neat plan and technically honorable while also being quite psychopathic.

Our particular knights of the Round Table were having none of this, of course, which ended up with them doing some quite horrible things: Ebert of Borsfort, the avoved materialist of the crew, went so far as to outright lie and mislead and plot and connive to ensure that poor Gawain would not even find the Green Chapel in time for his assignation. I found it hilarious how Ebert became the main antagonist of the story, entrapping the other knights with the hospitality of his great house – a very effective leveraging of his position as the Lord of a fief, I thought!

However, this was indeed not the full extent of the horrible crimes that he knights ended up committing, no doubt because they lacked a proper moral compass. Frustrated with Ebert’s ploy, the rest of the knights abandoned Ebert and Gawain to the hospitality of Borsfort with the intent of finding the Green Chapel by themselves and bullying the Green Knight into “letting Gawain go”. I found the moral justifications they built up for themselves both peculiar and amusing, as the knights concluded that really, the Green Knight was a villain who was trying to murder an innocent young man for a meaningless point of honor, and therefore they should all go and challenge the Green Knight to combat and kill him.

At the Green Chapel, at the appointed time, the knights discovered the Green Knight and found that the Knight was an infuriating idealist, unwilling to bend the knee to their threats of violence. It was quite dramatic and emotionally difficult to watch the player characters struggle with their honor, ultimately choosing the path of the mildest compromise: they were happy to extort an empty promise under duress from an unarmed man-thing to protect the honor of Camelot, but didn’t have the guts to outright slay the Green Knight and bury the whole matter.

However, the best was still to come: after they let the Green Knight go, one of the knights, the aforementioned Einar the Saxon, tracked the Green Knight through the snowy woods and found the track returning to Hautdesert, Lord Bertilak’s mansion. Armed with this knowledge Einar realized that the Green Knight wasn’t a mystic creature of the woods, but rather a man of flesh and blood. While the rest of the knights started on their return journey to fetch Gawain from Borsfort and return to Camelot, Einar damned his soul thrice over by assaulting Hautdesert, killing Bertilak in a duel and murdering his entire family to get rid of any witnesses.

Meanwhile, Ebert was entangling Gawain in a crime somehow even worse back in Borsfort: bribing a priest of an appropriate minute parish nearby, Ebert managed to convince Gawain that the local humble church was the Green Chapel intended by the Green Knight. Ebert’s cats-paw priest then convinced Gawain that the Green Knight thing was a divine test of courage that he had passed by choosing to arrive here despite knowing that the beheading game would cost him his life. Gawain’s great courage had, however, lifted a great yet otherwise generally unspecified dark curse from the chapel and the parish, praise Jesus!

So that was our version of the Green Knight’s tale: two hypocrites coerce a man with violence (the very most basic precept of Arthur’s chivalric code, broken), a third murders him and his family (a mortal sin, and a crime worth outlawry), and meanwhile a fourth engages in brazen blasphemy to mislead an honorable knight (the worst of these crimes for anybody with religious sentiment). The fun part is that this wasn’t murder-hoboing on the parts of the PCs, they just disagreed so very vehemently with the chivalrous premise of the tale that they couldn’t just stand by and witness what they expected to be a callous murder of an honorable knight. One thing led to another, and now they are all carrying some secrets that would, should they ever come out, cause them to be outlawed or worse.

My favourite part of the denouement was when Sir Bysador decided that he absolutely could not go back to Camelot: his own honor required him to bear witness to what happened, but the events at the Green Chapel were so horrible that he could not bear to report back to the High King on this, particularly as it endangered not only his own reputation, but that of his fellows. So Bysador decides to take the excuse of an adventure offered earlier and journey immediately to the north, to the Cymric lands, and thus temporarily avoid the situation. Percival joined him in his exile, leaving only the greater villains Einar and Ebert to return to Camelot with the triumphant Gawain. It’ll be interesting to see what they’ll get up to next time.

The summer sports season openeth

Part of my relatively high activity this week was caused by the increasingly sparse snowbanks in this part of the country. Lack of snow inspired me to call on some friends to go frisbee golfing; the theory is that an outdoors sport without close contact, engaged in with healthy people, probably won’t cause any of us to catch the plague. Apparently we weren’t the only people thinking this way, as there were some others at the Peltosalmi frisbee golf course as well despite the vast snow fields still covering places here and there. Not too much snow as long as you’d desist from specifically throwing a white disk into the snow fields, we found.

My frisbee golf result was, of course, completely atrocious, as one might expect for the first try of the season.

Later on the week, aside from the routine gymnastics, a new fatbike-type bicycle has been distracting me from sitting in the office. My father had this (relatively sporty for an 80-year old) idea of getting a fatbike, so I’ve been putting together and test driving that particular beast over the last few days. I’ve never driven a mountain bike, so taking the new bike over various natural terrain is pretty fun; it’s clearly a distinct set of advanced skills to manipulate a bicycle in non-road terrain. I could see myself doing a bit of that this summer, assuming my father doesn’t bogart the bike all the time.

Gentlemen on the Agora

Aside from acting as a platform for our game development discussions, what have those cunning gents on the Agora been up to?

- A contributor was interested in strategy games involving higher-order political and diplomatic concerns. The concept of “grand strategy” as a distinct category of strategic thought and wargame was discussed, with various example games briefly considered. It’s a compelling field of design, but a challenging one, and many of the classic games in the genre are notoriously difficult to play, with long play times and high requirements for the number of participants (so as to simulate complex independent-actor environments).

- We had an interesting little disagreement about media interpretation concerning a geek classic: what does Han Solo mean when he talks about parsecs in the Star Wars scene? Some contributors thought that the scene as filmed is reasonably clear about the parsec thing being in-character salesman bullshit, and therefore the text misuses the word “parsec” intentionally as part of Han bamboozling some country hicks; for others it was equally clear that either the scriptwriter doesn’t know/care what a “parsec” is, or they’ve chosen to write a poorly-considered little snippet of dialogue that leaves the audience more confused than entertained. What I found most interesting was that we didn’t reach a subjective agreement about what the scene actually shows: for some people that scene clearly tells a story about a bullshit artist, while for others that interpretation doesn’t exist in the text, so to speak. A good example of how the message of art emerges in interaction between the work and the audience.

- I’ve been reading a horror fantasy comic book about undead hunting recently, titled Hack/Slash (reasonably good early in its run), which turned into an interesting little discussion about various kinds of undead monstrosities and the people who hunt them. A contributor suggested a particularly interesting idea: what if a “monster hunter” was hunting undead creatures in an effort to discover a conscious creature capable of revealing information about the world or experience of Death? Sort of like Flatliners, a nice little idea. I was particularly enamoured by the implication of how an organization dedicated to this sort of death exploration in a setting with a magical cosmology would surely, certainly turn into a death cult over time. After all, one of the first things you’d discover in such research would surely, certainly be some ugly dark magic to retain your personal youth and vivacity; an organization faced with such temptation would be likely to discard pretensions of science in favour of serving the personal persistence of its membership.

- I held a sermon earlier this week about the evils of clockwork game design. This was directly inspired by my reading of Tommi’s alpha draft that I discussed earlier in the newsletter; while Tommi’s game doesn’t quite get there, I got a whiff of dead formalism in some of the ideas involved, and thus got inspired to theoretize in length about the difficulties that rpg design faces when embracing excessively mechanical game state loops. The gist of the matter is that if you create a game that does not need the fiction to move its numbers around, you’re creating something where the maintenance of a vivacious fiction is no longer a priority. Asking the players to expend a lot of effort in maintaining a complex mechanical clockwork runs into danger of them ignoring the fiction, and doubly more so if you actually design to make the fiction irrelevant. The clockwork game that releases you from the awful burden of having to interpret the fiction and make choices is a false lead, it doesn’t end up with a compelling game. (Which is not the same as saying the opposite, of course: freeform is not powerful either.)